Guest Blog Post by Julian Carter

The 2017 NOW festival events are presented in REDCAT, a decent size black box theater with a fancy lobby. It’s on the ground floor underneath a major symphony hall (the Disney, natch) and across the street from the Broad Museum of contemporary art—a top-notch address if you judge by the neighbors, and a space making some architectural claims about its place in the art world. The promotional materials on the REDCAT website reinforce the message that we are supposed to sit up and prepare to be impressed. But that’s not why we went. We’re in LA for the weekend and our host, who is deep in the LA dance scene, wanted to come. He had to be downtown anyway to meet a young person he knows through the LA LGBTQ center’s mentorship program, and also out of personal loyalty to choreographers Jeremy Nelson and Luis Lara Malvacías. He explains they’re a transcontinental couple, which means they almost never get to work together, and he wants to support their collaboration.

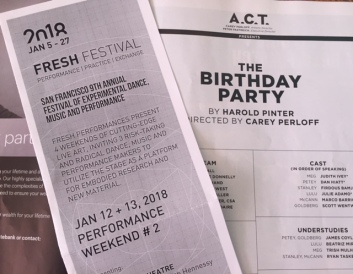

I agreed to tag along because I am interested in my friend’s mentorship relationship, and also because Nelson has a reputation as a truly marvelous teacher. I’m a touch ambivalent about a second piece on the program called “Butch Ballet.” My host is dreading it rather but I have some hope that its maker might be a person I met at a dance event last year and liked very much. I don’t quite recognize the choreographer’s name, but it all adds up to mean there is a consistent element of queer sociality and community in this outing. Before the show begins we’ve already agree to leave before the third piece on the program. We drove down from SF this morning, we’re too tired to stay out late, and the description suggests it’s going to be very loud.

- Screen Shot Retrieved on 8/30: https://www.redcat.org/event/now-festival-2017-week-three

Jeremy Nelson and Luis Lara Malvacías, “C.”

The piece opens with what turns out to be its strongest gesture: the two men springing softly into low, travelling hops with their feet in parallel at hip distance and their arms loose. These carry them around the stage in a sequence of loose squares, their feet landing first slightly in front of them, then to the sides and the back. Their feet create a satisfyingly steady 4:4 drumming as they land in emphatic unison on ONE, and more softly on the two-three-four, before their legs swing forward again to mark the downbeat.

The stage is black and bare save for a large screen on which is projected a 20 minute timer and an abstract pattern in green with some movement in it. There is also a potted plant hanging from the flies on a wire. This simplicity gives me a moment to appreciate that Jeremy has a remarkably fluid hop, his legs swinging underneath him with a powerful soft economy. Two stage hands—slender white men in black—come on and dress the stage with white furniture: a table, three chairs, a standing lamp—then leave again along lines apparently dictated by economy: the shortest route on, the shortest route off. The dancers stop their rhythmic bouncing, carry the objects offstage along the same efficient routes, and resume their soft explorations. The audience appreciates this with a laughter that I share. Everyone recognizes the collision of tasks and the need to clear a space for concentration. The stagehands return and repeat. The dancers repeat and return. There is no laughter this time. I normally like repetition and am curious to see how the choreographic relationship between these two contrasting kinds of task-based movement might develop; but it doesn’t get a chance. The music changes, the image on screen morphs into a blue sky with clouds, and the men stop bouncing.

To my mind, the piece could have, and perhaps should have, concluded at any point in this opening passage. The screen got darker and developed menacing imagery. The soundscape got louder and more aggressive. Clouds. Bombs. Fire. Contentious voices talking about God and hell and being an intellectual. For all the intensity of the material, the actual movement got less and less interesting to look at, in a way that made me think they were being deliberately anti-spectacular. I tried to get interested in that but failed. The dancers never connected with one another or with the objects on the set. There were some small exceptions: Jeremy hovered in the act of being about to sit on one of the chairs, for a few almost supernatural seconds that could well have been extended; at another point Luis moved the table just in time to catch a second plant that came hurtling down from the flies and landed with a thud. At the end they turned away from the house and fiddled with devices that lit a pile of vinyl upstage. The glowing result was partially projected onto one corner of the large screen. It seemed possible that there was a technical difficulty that prevented full projection, but since the pile was not very interesting to look at, I didn’t particularly miss its enlarged 2D version.

My notes scribbled on the program say: “it’s a good thing Nelson is such an accomplished mover” and “the less pedestrian the less interesting.” It’s true. The long passages of dance-y movement (in a generic kind of downtown NYC postmodern vocabulary) were so abstract that I found myself longing for the combination of intentionality and a simpler movement. I would happily watch Nelson brush his teeth, but I could not care about this dance. These artists have sufficient sophistication about the craft of making dances that they brought the thing to a close by returning to that initial springing bounce—this time while banging on small saucepans with sticks—yet the ABA’ structure wasn’t enough to justify the fifteen minutes in between. It looked to me as though the conceptual project of the collaboration had been allowed to take over the stage, with the result that any nascent aesthetic or affective communication with the audience got lost.

Gina Young, “Butch Ballet.”

In contrast, the limited charm of the second piece derived from its absence of polished craft, which made abundant room for the performance of identity earnestness and affective bonding between audience and performers. Here spectacle attempted to compensate for lack of craft and what appeared to be lack of intention about whatever craft was at the choreographer’s disposal. Five butches—or was that 4 butches and a transman? Or two butches, a transman, a lesbian and a nonbinary person? Or…

Anyway, five more or less butch people moved through a series of vignettes “about” female masculinity. Or so the program notes told me. There was bonding in a locker room; competition in a bar; playing video games as an inarticulate form of post-breakup emotional support; a swim party apparently intended to answer the perennial question of what a butch can wear to the beach; building a campfire; and three vintage dyke anthems, two of which were sung live and well. The little dramas seemed to suggest that the essence of female masculinity is an oscillation between competition and companionship with other butches. The exception came in the most developed vignette, which featured a large pink purse on a high table center stage. One butch began cooing to it to please hold her keys, then her phone and her this and her that; the others came out to add requests to hold notebook, pen, glasses, butch tears, fragile masculinity. The punchline: all the butches say “Can you hold all that?” and walk off.

The performers all seemed to be in their 20s, which might have something to do both with the ADHD pacing of the vignettes and with why my middle-aged companions and I felt a bit protective of them despite our boredom. We were also embarrassed, and even a little indignant. Out of kindness, we wanted to be generous; and equally out of kindness, we wanted to urge them to more rigor. But this wasn’t the place where we could have that conversation. As my friend hissed in my ear, “This isn’t Highways!”—that is, REDCAT isn’t a safe venue for queer identity work; and besides, in decades of going out we have seen this done infinitely better literally dozens of times, in community performace spaces where real creative risk-taking can land well. It was genuinely disappointing to see these people literally half my age repeating the same damn moves I and my peers made decades ago, with very minor development, despite the growth of institutional supports like the LGBT mentorship program that brought us to the neighborhood of this event in the first place, and the material and cultural resources that allow this performance to be staged in this expensive and prestigious space.

And yet at the end there was a rush of warmth from the audience, a sincerity of applause, that startled me for a fraction of a second before I recognized its inevitability. This again is something I’ve seen again and again since the 1980s: the overvaluation of predictable performance because it offers gender-minority bodies live on stage. Such offerings in queer spaces are risky because they so often rely on mobilizing a universal “we” that is easily exploded with simple questions about whose subjectivity, whose experience, whose embodiment is being offered as a mirror to the audience. And in straight venues, they risk presenting queer and trans modes of embodiment as tidbits for consumption in a way that leaves me both sad and mildly offended.

But beyond the question of presumptive audience, which is after all not entirely under the choreographer’s control, “Butch Ballet” displayed a disappointing lack of attention to the history and craft of making performances. Between several vignettes there was connective tissue provided by quotations from ballet class that seem to have been intended to highlight the performers’ butchness by presenting them in a situation conventionally associated with femininity. What it actually did for me was highlight Gina Young’s lack of thoughtful engagement either with choreographic technique or with the dancers’ actual individual capacities: several of these people were interesting to watch in different and potentially intriguing ways, none of which were drawn out for the audience to witness. For instance, in the vignette about inarticulate yet effective forms of emotional support between butch friends, one performer slouched onstage, took a seat on a bench facing us, and settled into a spinal C-curve to play an imaginary video game. The calm authority and naturalness of this posture were utterly persuasive, so that for a moment the audience got to be inside the screen, our attention focused on the competent grace of the hands extended toward us, manipulating imaginary Gameboy controls. But this performance had no interest in exploring task-based competency and the beauty it can create, preferring instead to imagine “dance” as ballet and ballet as a synonym for an outmoded system of gender discipline.

By the time “Butch Ballet” was done I was deeply relieved that we’d already agreed to leave before the third piece. Two weeks later, I’m still wondering about the imbalance between the resources that support the NOW festival at REDCAT and the quality of the arts experience we were offered. The REDCAT website is full of claims about fostering dialogue, yet the only connection I could find between the two pieces I watched was that one eschewed narrative and downplayed spectacle while the other relied entirely on those tools. Surely there’s a way to support experimental work by emerging artists while also curating potentially meaningful conversations.